On Free Comic Book Day, Something For Everyone

I don’t know what kind of comics you like. But I can say this much with certainty: When you visit your favourite comic store on Free Comic Book Day (which lands on May 4) you will find a veritable horn o’plenty to pick from. That’s right. There’s something for everyone. It’s an old-fashioned cornucopia. Or maybe a comicopia? What I mean is, whatever publisher, fandom, character, creator, title you favour, you will find something to scratch that particular itch. I say this after getting a sneak peak of the bulk of the freebies that await you at stores like my preferred comics haunt, L.A. Mood Comics & Games. Fandoms like Star Wars, Stranger Things, Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles, and Planet of the Apes are represented by offerings from publishing houses such as Marvel, Dark Horse, Titan, Fantagraphics, and IDW. Here are a few highlights from my reading to help inform your FCBD excursion:*For a sentimental old fool like me, the title that jumps out is Snoopy: Beagle Scout Adventures, a sampler with strips pulled from the collection of the same name landing in bookstores at the end of April. What ‘s better than Snoopy and Woodstock camping in the woods? Snoopy and a whole troop of little Woodstocks camping in the woods! *Marvel is putting on a big push on a couple fronts. One is this year’s companywide crossover, called Blood Hunt. The premise is that perpetual night has fallen on the Marvel Universe, which means it’s feasting time for vampires, including the hungriest bloodsucker of them all, Dracula. The other front is Marvel’s Voices line, which features characters and creators aimed at the queer, Indigenous and Latino communities. *The best cover may be the one on Tons of Strange, a child-friendly homage to the EC horror titles of the 1950s. Inside, you’ll find Jawas playing dice in the sands of Tatooine! *Speaking of the 1950s, Stories from the Atlas Comics Library includes a Stan Lee-penned piece in which the then-unknown creator took aim at Fredric Wertham. He’s the crank psychiatrist who provided the anti-comics crowd with pseudo-scientific cover for their crusade to ban comics, which included comic burnings, back in the day! *Also in the running for best cover is the one for Conan: Battle of the Black Stone, which features everyone’s favourite barbarian hefting a bloody axe. It comes from Heroic Signatures and Titan Comics. Is there a comics company out there that hasn’t published his adventures? The difference this time is the current licence holders are trying to situate Conan within a larger Robert E. Howard universe of characters. *Perhaps the broadest sampler pamphlet is the one featuring Asterix and Obelix, which includes episodes culled from seemingly every one of their books. Oh those wacky Gauls! *The Kill Shakespeare universe makes a return with Romeo Vs. Juliet, which imagines the star-crossed lovers crossing swords! How is this possible? It turns out Juliet faked her own death. No word in this promo pamphlet on how Romeo managed to shuffle back onto this mortal coil. *The Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtle handout includes a slice-of-life tale in which Master Splinter has a rare evening of quiet away from his adopted mutant sons. All I will say is that the rodent sensei doesn’t spend all his free time meditating!*The Cursed Library Prelude takes place in the Archie Horror world, so for those who prefer the dark side of Riverdale, prepare to meet Jinx, the daughter of Satan himself! It also features a snippet of a ghost story starring Archie’s favourite blond, Betty Cooper! So if you’re a fan of Venom, Flash Gordon, Johnny Quest, ThunderCats, Hellboy, Frankenstein’s wife or Mei-Mei the red panda, there’s something for you this FCBD. And that’s just the free comics . . . I hope you’ve been saving your shekels because the annual event is also a great excuse for London’s comic retailers to offer customers some outrageous deals!I love FCBD, dubbed Geek Christmas by some, for the feeling that’s in the air around town. It’s kind of like a moving fan convention as Forest City comic enthusiasts, cosplayers and pop-culture followers travel around our community, checking in at all the different stores. There’s a rare convergence this time as FCBD and May the Fourth (the day unofficially set aside to celebrate all things Star Wars) coincide, so there’s bound to be the waft of bantha steaks in the air. Don’t miss it! Dan Brown has covered pop culture for more than 31 years as a journalist and also moderates L.A. Mood’s monthly graphic-novel group.

Comics vs. Graphic Novels

By Dan BrownWhen is a comic book not a comic book? When it’s a graphic novel.And what the heck is a graphic novel? Your guess is as good as mine.Comic lore has it the term was invented by legendary creator Will Eisner. I get the impression Eisner – known for the Spirit newspaper strip – couldn’t sell illustrated stories to a legitimate publisher as comics, so he came up with the “graphic novel” label solely as a way to sell them.So it was a marketing gimmick from the get-go.I am old enough to remember comics before the advent of the graphic novel. Eisner’s A Contract With God came out in 1978, the irony-in-hindsight being that it isn’t a novel, but a collection of four short stories.But as a graphic novel, it has some kind of heft it didn’t carry as a comic – even though it’s a sequential story told with pictures, panels and text. Isn’t that the definition of a comic? It landed differently owing to the elevated subject matter – just dig that title.Current editions of A Contract With God proclaim its place in comic history. Does that mean anyone who cracks the book reads it in a different way than a “mere” comic? I don’t think so.What maybe shouldn’t surprise anyone is how Marvel got on board with the term fairly quickly. By 1982 Stan Lee and friends were trumpeting The Death of Captain Marvel as one of Marvel’s first forays into graphic-novel territory. It had a unified storyline and was bigger and more expensive than the monthly mags of the time, but used characters from the company’s superhero line.Meanwhile, another important thing was happening in the background. Harvey Pekar had started publishing the comic series American Splendor in 1976. His appearances in the 1980s on David Letterman’s show may have been how he caught my attention.Pekar is important because he was using comics in a revolutionary way: To tell everyday stories, rather than put a spotlight on costumed do-gooders. It was all about the mundane, a staggering departure at the time.I read stories like The Watchmen or Dark Knight Returns in serial form. They are now known as landmark graphic novels, but when I was experiencing them one month at a time I never predicted they would eventually be collected in anthology form. Pretty much all comics are now published with an eye to the eventual graphic novel.So somewhere along the line Pekar’s innovative insight – comics can be used to tell any kind of story – got grafted onto the emerging use of graphic novels to tell more “serious” superhero tales.And a genre was born. I’ll grant that I may be the only person who cares about questions like this. Maybe I’m the only individual demented enough to care. And I guess as long as graphic novels and comics are experienced as a printed or online product meant to be read, the distinction doesn’t matter.I originally started writing a weekly column about graphic novels because the industry had reached a saturation point – there were enough graphic novels coming out, I could potentially review a new one every week. We’re now at the point in the history of the medium where I tell graphic-novel newbies, “If there is a topic or issue that interests you, there is a graphic novel out there for you.”Oh, and I know I left out a bunch of other definitions. What is a cartoon? What is a newspaper comic strip? What is a Sunday funny? A web comic?All fodder for future columns.Until then, I would love to hear your thoughts in the comment box below.Dan Brown has covered pop culture for more than 31 years as a journalist and also moderates L.A. Mood’s monthly graphic-novel group.

Snoopy is Trapped Behind Enemy Lines

By Dan BrownI’m not much of a Charlie Brown fan, but I freaking LOVE Snoopy.So it’s not surprising an old Peanuts strip featuring the beagle with a vivid imagination caught my eye when it washed up in my Facebook feed last week.The strip, which originally appeared on October 2, 1966, features nothing but panels of Snoopy walking. And walking. Finally, there’s a punchline in the ultimate frame, and by that point the reader knows all of human experience is contained in that one Sunday strip.Let me explain.Having been born a couple years after that strip first appeared, Snoopy and his pals have been a constant in my life, and I consider Charles Schulz to be an artist of the highest order. As an adult, I belong to any number of Facebook groups that re-circulate Peanuts strips because I like to be surrounded by Schulz’s work. For whatever reason, lately I’ve really been grooving on Snoopy’s adventures as a Sopwith Camel pilot during the First World War, particularly the time he spends out of the cockpit. It doesn’t matter to me he might be imagining the whole thing. Part of the charm is how Schulz never really made it explicit whether Snoopy’s air battles in the Great War were “real” or not. So how could something as simple as a newspaper cartoon strip rock my world? I’ll describe it to you.The strip is 15 panels long, most of them narrow. A forlorn figure with flying goggles perched on his forehead trudges along. He goes through a forest. He crosses a stone bridge.His paws tread over an unplowed field. Snoopy crosses a stream (in this panel, you can see the debt Bill Watterson’s Calvin and Hobbes owes to Peanuts). The little white-and-black dog scrabbles up and down hills.He walks by the light of the moon. He pauses under a tree as he bakes under the scorching sun. He passes through tall grass, then goes around a fence. He is alone – not even Woodstock, his best bird friend, has accompanied Snoopy on this long journey.Exhausted, he crashes to the ground. Propping himself up against a rock, Snoopy thinks to himself, “They’re right . . . It IS a long way to Tipperary.”Funny, right?But here’s the thing: Snoopy is not in Ireland. The unspoken part of this particular cartoon is he’s behind enemy lines, trying to get back to his unit in allied territory. He’s been shot down. That’s why he’s travelling even at night. He is utterly alone, surrounded by enemies who want to do him harm. The question isn’t if he will get to Tipperary, but if he will reach safety. Snoopy’s weariness at the end comes from fear as much as the prolonged hike.What can I say? When I realized his predicament, I nearly cried.The mark of an artistic genius is that he can move his or her audience. After reading this strip, I was genuinely concerned for Snoopy. The forced march is a metaphor for life.In fact, it’s not overstating the case to say I felt a kinship with the cartoon canine because the promise of mortality – that one day, we will all experience death – hangs over every panel.You might say, well it’s all in Snoopy’s head, but it doesn’t matter: The truth is the fear and exhaustion are real. They jump off the page.So you can have your so-called great art. You can have your pyramids, your Sistine Chapel, your jazz music, your abstract paintings, your orchestras. I’ll take 15 panels from Charles Schulz over all of it.Dan Brown has covered pop culture for more than 31 years as a journalist and also moderates L.A. Mood’s monthly graphic-novel group.

Make mine Byrne

What you probably don’t know about the Forest City is how it’s the hometown of the leader of the Marvel comics superhero team Alpha Flight.That’s right, James (Vindicator) Hudson hails from London, Ontario.This bit of trivia is on my mind because last October the company re-released the Alpha Flight comics by John Bryne Omnibus, which collects the team’s early exploits in its own title and others from the 1970s and 1980s.I’m almost 600 pages into the hefty tome, which clocks in at 1,248 pages long. Being a fan of Byrne, the sometime Canadian artist/writer, obviously I love the thing.I began following his work earlier in the Me Decade when he penciled titles like Doomsday+1 and Space: 1999.What can I say? Something about his precise, elongated lines spoke to my younger self. I was part of the generation whose puppy love for superheroes grew into something deeper when Byrne was assigned to such Marvel titles as Iron Fist, Team-Up and, of course, the Uncanny X-Men.We were Wolverine fans before the Canadian X-Man became an unkillable killing machine. And we were thrilled when Wolvie’s former allies, Alpha Flight, got their own series.What we didn’t know was Byrne did not have a fun time doing the first 29 issues of Alpha Flight, which appear in this collection along with their appearances in mags like the Incredible Hulk, Machine Man and Two-in-One. For a while there, the Alphas – Sasquatch in particular – were perpetual Marvel guest stars.As he has stated in interviews in the years since, Bryne was frustrated with the limits of Canada’s own super-team. All Alpha Flight had been created to do, he famously noted, was to survive a fight with the X-Men. They were flimsy, two-dimensional.Some fans have pointed to how Bryne would kill off major characters as evidence he had soured on the character. Which didn’t stop the title from selling. Indeed, his first royalty check for Alpha Flight, at a time when royalties were not standard practice at Marvel, was reportedly the biggest Marvel had issued to that point.What jumps out at me in the omnibus edition?*Wolverine had his roots as a mortal character. In one X-Men story collected here, he even gets winded from running a lot. That destructible version of the character is long gone.*Byrne has spoken of how he always wrote Northstar true to his sexuality, even before Marvel was ready to reveal him as the company’s first queer superhero. It checks out. From the vantage point of being an adult reader, it’s clear Northstar is gay.*Vindicator, who changed his name to Guardian, was just getting interesting before he died in action.*I love Byrne’s depiction of Canada as home to ancient evils. He handled both pencils and inks on Alpha Flight, which means each panel lacks the background detail of when Terry Austin was inking his work in X-Men.*The issues here have a good balance of magic-driven storylines, street-level adventures and out-and-out superheroics. A favourite Byrne villain, the Super Skrull, even makes an appearance.*Each issue raises as many questions as it answers. Byrne was doing a superb job, given the constraints of monthly comics, of adding layers to each character. Keep in mind he was in the middle of a long run on Fantastic Four at the same time he launched Alpha Flight. All in all, the Alpha Flight by John Byrne Omnibus is a worthwhile trip down Memory Lane for any comic fan who grew up Marvel.Dan Brown has covered pop culture for more than 31 years as a journalist and also moderates L.A. Mood’s monthly graphic-novel group.

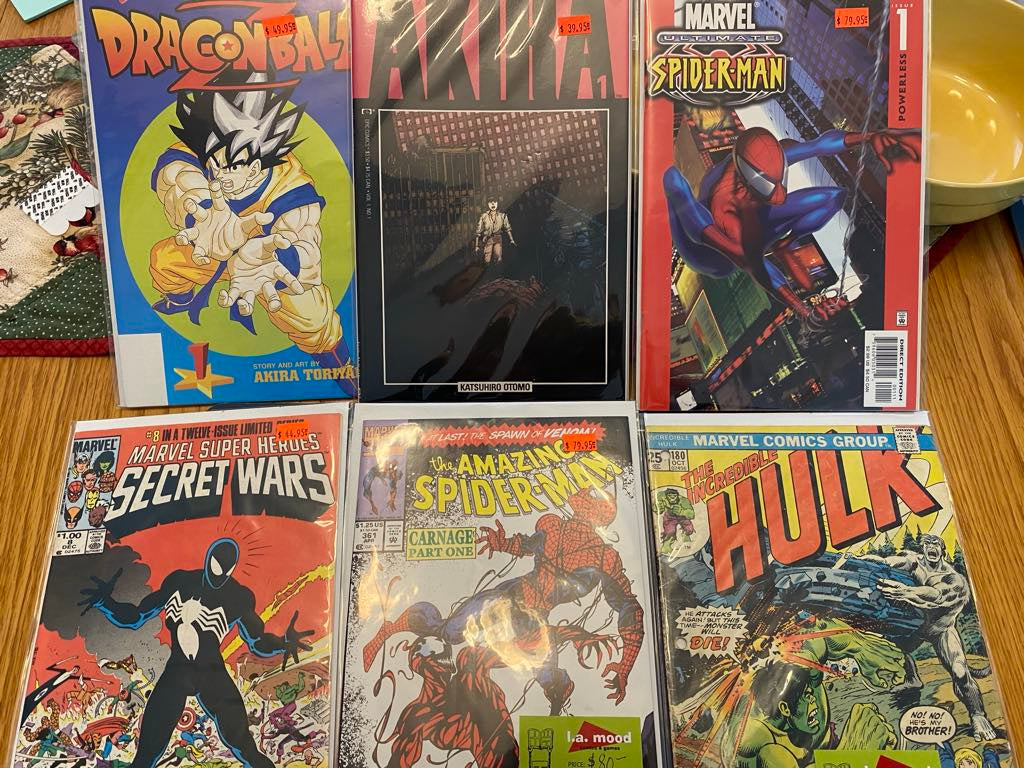

New Comic Collection on Sale Starting Saturday, February 17

We just purchased another great new collection of comic book back issues! This collection includes CGC graded and non-graded issues.The collection includes hundreds of back issues. Comics include Spiderman, X-Men, Transformers, Daredevil, Dragon Ball Z, Avengers, Captain America, The Hulk, and more. This collection will only be available in store. Visit early and buy before they are all gone!L.A. Mood Comics and Games100 Kellogg Lane, Suite 5London ON N5W0B4, Canada

This is a Golden Age for Comics

Let me begin by making a bold statement.There has never been a better time in human history to be a fan of comics than now.The Golden Age of Comics is upon us. Don’t let anyone tell you otherwise.There has never been a greater variety of comics dealing with a multitude of subjects. Comics art has never been better. Plus comics are finally being taken seriously as a form of expression. And there are more opportunities to discuss comics and appreciate them than at any time before.Don’t believe me? Imagine a time when most of the comics on the spinner rack at your local drug store were published by two companies. They were all dismissed as stuff for children. There was no such thing as graphic novels, no major publisher looking for sustained narratives that weren’t about heroes with superpowers. And if you wanted to share your love of comics with fans around the world, you had no outlet to do so.I grew up in such a time. It was called the 1970s. Trust me, things were not better in my day. Back then, the general view was that comic books were something children grew out of. Why didn’t Stan Lee use his real name when he helped create the Marvel Universe? Because he was saving it for his attempts at “serious” literature.Nor was he the only one, as creators were made to feel embarrassed about working in an industry not treated like a legitimate trade. When new comic books came out, they weren’t reviewed in the newspapers of record. Movies featuring costumed do-gooders were few and far between.Fast-forward to 2024. Things are so much better in so many ways.Comics and graphic novels are recognized as a valid medium for telling all kinds of stories, not just ones about guys and gals in tights.Want to write about what it’s like to work in Alberta’s oil sands? Want to recollect your teen years toiling in a pulp and paper mill, dreaming of being a cartoonist? Want to explore the effects of an autocratic government in North Korea? Want to recount your hilarious attempts to capitalize on the “vinyl resurgence?” All of those stories have been told in graphic novels by Canadian creators. It’s true superhero comics did have a mass audience in the 1940s among children, but let’s suppose you’re a fan today of a particularly obscure character – say Marvel’s Rocket Raccoon. If you want to learn more about him, there are entire monthly titles devoted just to his exploits, featuring only him without any of his Guardians of the Galaxy teammates. Plus you can buy action figures and every other possible piece of merchandise based on Rocket.In fact, thanks to big-budget motion pictures and streaming shows, superheroes are more central to our culture than they were even back in the post-Second World War period. These productions feature serious talents like Robert Redford, Cate Blanchett, Jack Nicholson and Natalie Portman.The New York Times wasn’t reviewing comics or graphic novels when I was falling in love with them as a kid growing up in small-town Ontario. Academics weren’t doing serious research on them. There wasn’t a Scott Pilgrim or Sweet Tooth series on Netflix for me to enjoy, because none of that infrastructure existed.Nor did we have creators like a John Porcellino, whose work is so perfect that I consider it poetry in the form of sequential panels. Hey, I still love the Marvel mags of my childhood, but they weren’t that creative. And now we have a dedicated network of retailers like L.A. Mood devoted to selling comics, connected by a global-information source that gives everyone the tools to express their love for whatever title or character or storyline they fancy. If you like a property, there’s a website for it. All of which is bolstered by a group of in-person events – here in London, that includes Free Comic Book Day, Forest City Comicon, and Tingfest. One of the big secrets in life is to know you have it good WHEN you have it good, not later. As the song says, you don’t know what you got till it’s gone, so my advice to anyone reading this column is to revel in this current Golden Age while it lasts.Dan Brown has covered pop culture for more than 31 years as a journalist and also moderates L.A. Mood’s monthly graphic-novel group.