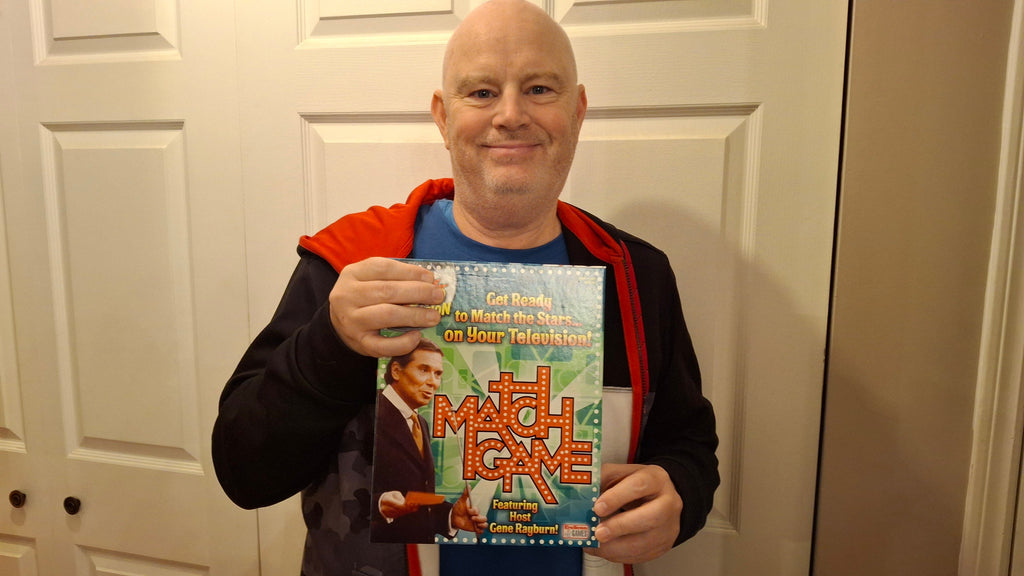

Game Show Hosts Have It All

By Dan Brown Game-show hosts fascinate me. Not so much their on-screen personas (although I think it takes great skill to host a quiz show), but more their lives off-screen. What are they like in person? What do they do when they’re off the clock? Is each one slowly going insane due to the same witch’s brew that has been the doom of many an entertainer – an excess of cash and free time? I’ll admit up front I haven’t hosted a game show myself, nor have I appeared on one. I did interview Alex Trebek once when he came to Toronto in the 1990s for a cattle call in Toronto to drum up interest in appearing on Jeopardy! I also auditioned, failing to make it even as far as the first round. In the same decade, I also interviewed Ben Stein and Jimmy Kimmel (then co-hosts of Win Ben Stein’s Money). As well as such game-show regulars as Charles Nelson Reilly and Betty White, when Match Game’s Gene Rayburn died. Most of what I know about game shows, and the dudes who preside over them, comes from being a regular watcher of programs such as Wheel of Fortune, Family Feud, and Remote Control. The guys with the perfect hair and whiter-than-white teeth are handsomely paid for their services, which is as it should be. I’ve done a tiny amount of broadcast work so I can confirm that being a so-called “traffic cop” whose job is to welcome contestants, make small talk, ask questions, then move the players through the different stages of an individual episode is so much harder than it looks. And to do that with panache, day after day, is a skill few people have. They make it look easy. Five years ago, Newsweek reported Trebek earned $18 million a season. That figure puts him up there with some of the highest-paid entertainers on the small screen. Nor does that sum take into account the bucks he brought in from his other gigs, like being a spokesman for insurance companies. And unlike talk-show hosts, a guy like Trebek didn’t work all year long. Again, depending on the news source you find, he worked maybe two months out of 12 (or the weekly equivalent) taping an entire season of the long-running quiz show. The questions such a lifestyle raises are obvious. What do they do with all that time off? And with pretty much unlimited resources, what do they do to keep themselves amused? Most importantly, how do they keep themselves out of trouble? Idle rich hands, the conventional wisdom goes, are the playthings of the devil. There are some game-show hosts, the late Bob Barker to name one, who had causes they supported when not on the set. Barker, famous for his neuter-or-spay spiel at the conclusion of every showcase showdown, found focus in lending his star power to organizations that were devoted to animal welfare. It gave him something to do. However, the cause can’t be so off-the-wall that your work as a celebrity endorser takes the spotlight off your main money-maker. Pat Sajak is into conservative political causes, but you rarely heard about it when he was hosting Wheel of Fortune because he didn’t want his extracurricular activities to draw attention away from the show. I should also mention that most of these programs are filmed in California, so it would be easy for your typical American male to go to seed quickly in those surroundings. I liken them to rock stars, another group that is highly paid, but also has to contend with bags of downtime. Boredom plus money has been the end of many a promising career in the musical world. Luckily for us working schlubs, we never have to worry about how to give our existence a purpose. We’re too busy working our slaving jobs to get our pay to think about the meaning of life. Dan Brown has covered pop culture for more than 33 years as a journalist and also moderates L.A. Mood’s monthly graphic-novel group.

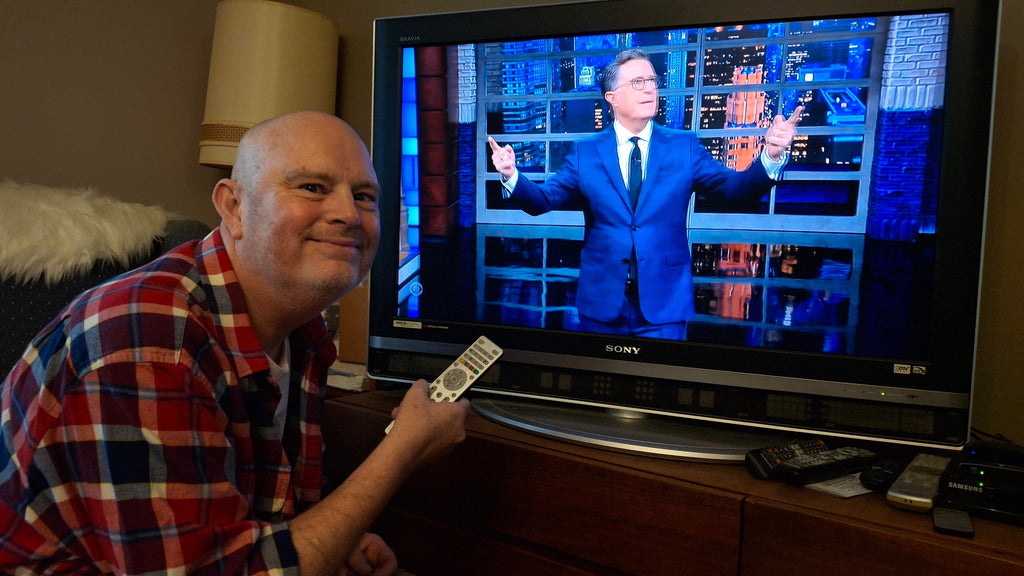

Network Talk Shows Are Played Out

By Dan Brown Given the fuss over the axing of the Late Show With Stephen Colbert, you might get the impression network talk shows matter. They don’t. Such programs haven’t mattered for years, and few TV viewers would notice if ALL of them went off the air. The format of a monologue, phony interviews, then a musical performance is played out. In a world in which seemingly every slightly famous person hosts a podcast, network talk shows are not the draw they once were. When was the last time you watched an episode of Colbert from start to finish? What about the likes of Jimmy Fallon, Jimmy Kimmel, or Seth Myers? Contrast those guys with Johnny Carson. He was such a fixture back in the day that his retirement from late night in 1992 amounted to a cultural earthquake. Carson’s heyday was a different era. Network TV ruled the roost, with cable coming on strong. When the Carson-inspired David Letterman took off in the 1980s, his brand of late-night comedy was considered edgy, dangerous, subversive. You WANTED to stay up late to see what Dave was up to. Fast-forward to 2025 and it feels as though the list of celebrities who have hosted a late-night chat show at some point in their careers is longer than the list of those who haven’t. They aren’t special anymore. No one is interested in watching a procession of minor stars fake their way through a pre-scripted interview to promote their latest project. We can get our entertainment news in so many different places now, and the supply of celebs far outstrips the demand. The last late-night interview that mattered aired in 1995, when Jay Leno got to ask Hugh Grant why he had hired a prostitute named Divine Brown days earlier: “What the hell were you thinking?” in 2025, no one is eagerly anticipating the next guest who will step out from behind the curtain. Networks have hung on far longer than anyone thought they would, but according to the Los Angeles Times, the proportion of the television viewing audience watching streaming is now larger than that watching linear TV. Talk shows were relatively cheap to make when companies actually advertised their wares on network TV. In their day, they had cultural sway. A new generation has taken the format and is running with it, doing interesting things online. The idea of an interview show with the guests all eating spicy hot wings might sound loony, but it actually works. Or how about a parody of talk shows called Between Two Ferns on which every interview is hilariously uncomfortable? Maybe you would rather watch yet another minor movie actor talk about what a great time they had on set making the latest programmatic Hollywood sludge. You’re in a shrinking minority. If talk shows on network TV have accomplished anything down through the decades, they’ve killed interviewing as an art form with their rehearsed conversations. Which is OK. With a million podcasts to choose from, none of which are time-limited, on any number of platforms, we’ve got space for all the genuine follow-up questions imaginable. That’s where the real talk is taking place with hosts who don’t need to feign their interest. Oh, and just for the record, the best talk show ever was on pay TV – it was called Night After Night and was hosted by Allan Havey with sidekick Nick Bakay in the early 1990s. I taped it every night. So let’s retire network talk shows — all of them. At least for a few years or decades. Letting the genre lie fallow for a while can only lead to positive things for the entertainment industry. Dan Brown has covered pop culture for more than 32 years as a journalist and also moderates L.A. Mood’s monthly graphic-novel group.

Pop Culture Like Star Trek Used to be Disposable Fluff

By Dan Brown When I say “Star Trek,” I mean the old TV show that featured William Shatner as Captain Kirk and Leonard Nimoy as Mister Spock. I don’t mean the Next Generation or Voyager or Upper Decks or Strange New Worlds or anything else. And if you’ve seen a Star Trek rerun in the last few years, you’ll have noticed the special effects stand up remarkably well. Although it was made on a shoestring budget in the late 1960s for an audience that had low expectations of science-fiction television, those shots of the Enterprise look crisp. But here’s the thing: Those aren’t the original effects. When you see the Enterprise floating in space, fighting a battle, or high above a planet’s surface, those images were inserted into the original episodes in a remastering process that dates back only to 2006. So the Trekkies who fell in love with the series in the 1960s did so without the attraction of modern special effects. My purpose here isn’t to argue which version is better. Nor is it to speculate if Star Trek creator Gene Roddenberry would have approved of the new effects (he died in 1991). What I want to point out is how the revised Star Trek episodes represent a new attitude toward pop culture. What would surprise Roddenberry if he were alive is how long-lived his show has been. When the program originally aired from 1966 to 1969, TV didn’t have a great reputation. The medium was derided as “the boob tube” because the dominant perception was that the small screen appealed to those who weren’t all that bright. Consequently, Star Trek – which many consider classic stuff today – was just as disposable as any other show on the air at the time. In other words, despite embodying enduring social and political themes, individual episodes weren’t built to last. It didn’t matter back then if the show would hold up to repeated viewings, and I’m guessing the idea people would still be watching Star Trek in the year 2025 would have startled network executives. Nor is Star Trek the only example of pop culture that was created as ephemera that has far outlasted its creator’s intentions. Star Wars (by which I mean the movie with that title that came out in 1977) was made at a moment when few moviegoers were willing to pay to see a particular film multiple times. After all, a child’s ticket went for a whopping $1.50! Who could afford that in the hardscrabble Seventies, no matter how much you loved a film? As you likely know, several new coats of digital paint have been applied to Star Wars in the interim. There were versions with enhanced sound effects, then versions with enhanced visual effects, and on and on. They may have even released a 3D Star Wars for all I know. It doesn’t stop there. There are also updated editions – with outtakes put back in – of novels like George Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four and Stephe King’s ’Salem’s Lot. Albums such as Bob Marley’s Legend have likewise been retouched. The important thing to note here is our feelings about pop culture like the original Star Trek series have changed: What was once a throwaway indulgence meant only for a moment’s pleasure is now taken seriously, even expected to transcend its time. Heck, there are even such journalists as Rob Salkowitz who specialize in writing about pop culture! That didn’t used to happen. Expectations have risen dramatically. You could even argue it’s pop culture like Star Trek and Star Wars that is partly responsible for creating an audience that wants more out of its TV, movies, music and so on, than a momentary distraction. Me, I prefer the “original” versions of things that were released back in the day. To my eyes, the first Star Wars motion picture had a certain low-budget charm so I didn’t need a new, “better” one. But I’m glad it’s still around, even in a modified form, to light the fire of imagination in the minds of a new generation of pop-culture enthusiasts who have higher expectations than I ever did. Dan Brown has covered pop culture for more than 32 years as a journalist and also moderates L.A. Mood’s monthly graphic-novel group.

Pop Culture Like Star Trek Used to be Disposable Fluff

By Dan Brown When I say “Star Trek,” I mean the old TV show that featured William Shatner as Captain Kirk and Leonard Nimoy as Mister Spock. I don’t mean the Next Generation or Voyager or Upper Decks or Strange New Worlds or anything else. And if you’ve seen a Star Trek rerun in the last few years, you’ll have noticed the special effects stand up remarkably well. Although it was made on a shoestring budget in the late 1960s for an audience that had low expectations of science-fiction television, those shots of the Enterprise look crisp. But here’s the thing: Those aren’t the original effects. When you see the Enterprise floating in space, fighting a battle, or high above a planet’s surface, those images were inserted into the original episodes in a remastering process that dates back only to 2006. So the Trekkies who fell in love with the series in the 1960s did so without the attraction of modern special effects. My purpose here isn’t to argue which version is better. Nor is it to speculate if Star Trek creator Gene Roddenberry would have approved of the new effects (he died in 1991). What I want to point out is how the revised Star Trek episodes represent a new attitude toward pop culture. What would surprise Roddenberry if he were alive is how long-lived his show has been. When the program originally aired from 1966 to 1969, TV didn’t have a great reputation. The medium was derided as “the boob tube” because the dominant perception was that the small screen appealed to those who weren’t all that bright. Consequently, Star Trek – which many consider classic stuff today – was just as disposable as any other show on the air at the time. In other words, despite embodying enduring social and political themes, individual episodes weren’t built to last. It didn’t matter back then if the show would hold up to repeated viewings, and I’m guessing the idea people would still be watching Star Trek in the year 2025 would have startled network executives. Nor is Star Trek the only example of pop culture that was created as ephemera that has far outlasted its creator’s intentions. Star Wars (by which I mean the movie with that title that came out in 1977) was made at a moment when few moviegoers were willing to pay to see a particular film multiple times. After all, a child’s ticket went for a whopping $1.50! Who could afford that in the hardscrabble Seventies, no matter how much you loved a film? As you likely know, several new coats of digital paint have been applied to Star Wars in the interim. There were versions with enhanced sound effects, then versions with enhanced visual effects, and on and on. They may have even released a 3D Star Wars for all I know. It doesn’t stop there. There are also updated editions – with outtakes put back in – of novels like George Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four and Stephe King’s ’Salem’s Lot. Albums such as Bob Marley’s Legend have likewise been retouched. The important thing to note here is our feelings about pop culture like the original Star Trek series have changed: What was once a throwaway indulgence meant only for a moment’s pleasure is now taken seriously, even expected to transcend its time. Heck, there are even such journalists as Rob Salkowitz who specialize in writing about pop culture! That didn’t used to happen. Expectations have risen dramatically. You could even argue it’s pop culture like Star Trek and Star Wars that is partly responsible for creating an audience that wants more out of its TV, movies, music and so on, than a momentary distraction. Me, I prefer the “original” versions of things that were released back in the day. To my eyes, the first Star Wars motion picture had a certain low-budget charm so I didn’t need a new, “better” one. But I’m glad it’s still around, even in a modified form, to light the fire of imagination in the minds of a new generation of pop-culture enthusiasts who have higher expectations than I ever did. Dan Brown has covered pop culture for more than 32 years as a journalist and also moderates L.A. Mood’s monthly graphic-novel group.