All the President's Men continues to Inspire

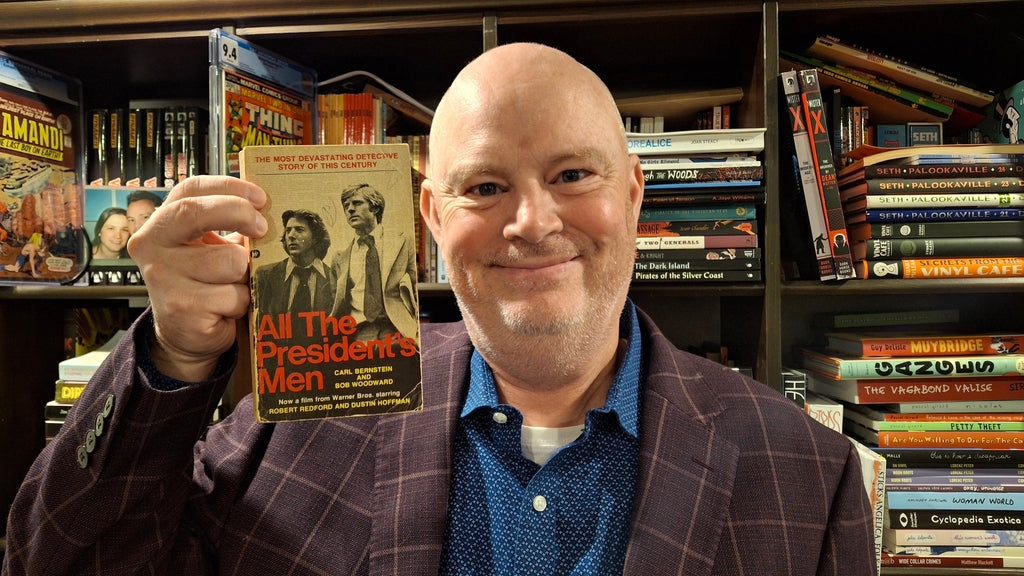

By Dan Brown After Robert Redford died on Sept. 16, the accolades came pouring in. He was remembered as a legendary actor, director, advocate for the environment, and founder of the Sundance Film Festival. What the rest of the world might not know is Redford also has a special place in the hearts of journalists of my generation. Even if you’re not a journo, you likely know Redford played real-life Washington Post reporter Bob Woodward to Dustin Hoffman’s Carl Bernstein in the 1976 feature-film adaptation of All the President’s Men, the duo’s account of their Watergate reporting, which ultimately led to Richard Nixon resigning as U.S. President. Redford fought to get the motion picture made. People told him Watergate was old news, that the country needed to move on in the aftermath of its long national nightmare, that a story about two journalists doing long hours of research wouldn’t play well on the big screen. But it did work, and All the President’s Men – the movie – is still inspiring media professionals all these decades later. It’s a journalism classic, and a perfect example of a 1970s paranoid thriller. I often turn to All the President’s Men – the book – to help inspire the young journalists I mentor at the Western Gazette, and teach at Western University. The worn paperback copy I have on my bookshelf has a picture of Redford and Hoffman on it, not the less photogenic Woodward and Bernstein. I like to remind my mentees and students that the two reporters, both in their 20s, weren’t all that much older than them when the Post helped to bring down Nixon. The book is a testament to the power of old-fashioned shoe-leather journalism. It wasn’t AI that helped the pair to trace the Watergate burglary back to the Oval Office, nor was it the internet. How primitive were the reporting tools back in the early 1970s? Heck, Woodward and Bernstein didn’t even have voicemail, it being the era of rotary telephones. What they did have was time, the most valuable resource to a journalist. Neither one of them had much of a social life, so their competitive advantage was that they came into the newsroom on weekends and stayed late in the evenings. I also remind my young charges how Woodward and Bernstein made mistake after mistake. They were swimming in uncharted waters, so the journalism textbooks of the day were no use to them. Luckily for America, they were smart enough to learn from their mistakes. They did have institutional support in the form of top Post editor Ben Bradlee. When the paper was attacked by the White House, it was Bradlee who crafted the Post’s response: “We stand by our story.” All journalists should be so lucky to have that level of confidence from their boss over a prolonged period – keep in mind Nixon didn’t quit until two years after Watergate, when the Republican brain trust on Capitol Hill told him he wouldn’t survive an impeachment conviction vote in the Senate. All the President’s Men belongs in the film canon along with the likes of the Parallax View, Network and Capricorn One. For a country that was so disillusioned, it provided a tonic by showing two regular guys who were determined to get the truth about Watergate out to the masses. Judging by recent events south of the border, it’s a message that is as crucial now as it was then. Other journalism movies I recommend: The Paper, Spotlight, Shattered Glass, Broadcast News, The Killing Fields, The Insider, Citizen Kane, Salvador, Frost/Nixon, Almost Famous, and Anchorman. Would love to hear about your own favourites in the comment box below. Dan Brown has covered pop culture for more than 33 years as a journalist and also moderates L.A. Mood’s monthly graphic-novel group.