It’s Easy To Beat Up On Graphic Novels

By Dan Brown

Who will stand up for comic books?

I’m thinking about this question after Alberta Premier Danielle Smith ordered school libraries in that province to pull books with pictures of “pornography” in them (her word).

“What we are trying to remove are graphic images that young children should not be having a look at,” Smith added after the original ministerial order from her government blew up in her face.

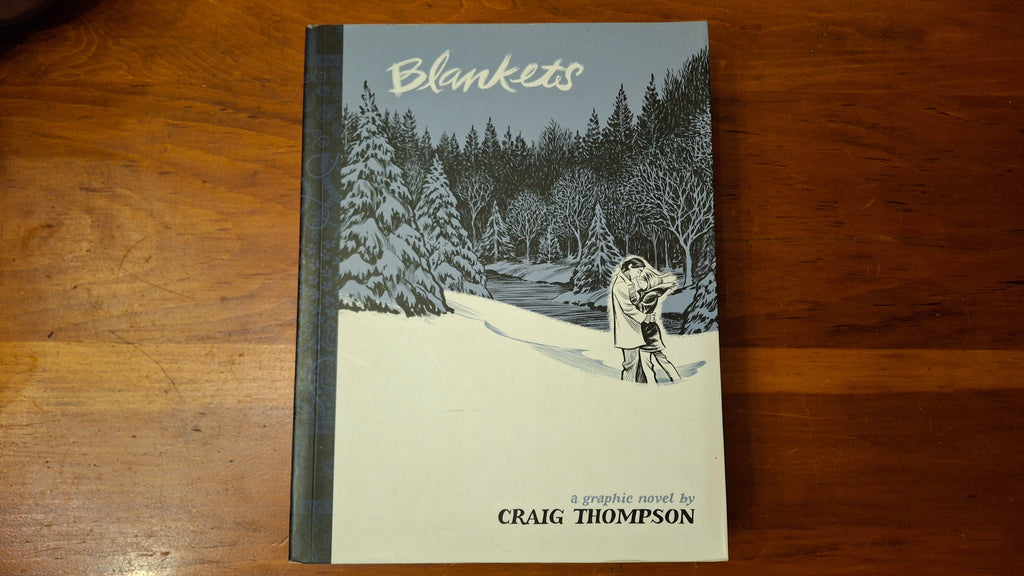

From what I’ve read, there are four specific graphic novels that have raised Smith’s ire: Craig Thompson’s Blankets, Alison Bechdel’s Fun Home, Mike Curao’s Flamer, and Maia Kobabe’s Gender Queer.

I’ve read only one of those books, Blankets, and I recall it as an earnest attempt by Thompson to describe his struggles growing up in a fundamentalist Christian home. Perhaps Smith doesn’t like it because – spoiler warning – it ends with Thompson leaving the church.

The other three books have one thing in common: The sex they depict isn’t between a man and a woman, but same-sex partners.

Of course, Smith isn’t the first person to pick on comic books.

Hating on comics is a tradition that goes back decades, extending back to the era when the audience for comics actually was children. These days, the typical Marvel or DC reader is a dude in his forties or fifties.

You may have heard of Fredric Wertham, the notorious crank psychiatrist who campaigned against comics in the 1950s. It’s hard to believe now, but there were actual Congressional hearings in the U.S. into how comics were unfit for America’s kids. There were also comic-book burnings.

Among his complaints with comics was Wertham’s feeling they were too violent, thus making young kids into juvenile delinquents.

He also thought they turned straight kids into gay ones. Wertham hinted there was something going on between Batman and Robin between the panels, and even wrote a book detailing his research, which was thoroughly debunked years ago.

But Seduction of the Innocent did have a major impact, with the comic industry opting for self-censorship in the form of the Comics Code, which lasted until 2011.

How ridiculous was the self-censorship regime? A comic was once rejected by the Comics Code Authority censor on the basis of writer Marv Wolfman’s last name being in the credits, since the Code forbade mentions of the occult like, you know, wolfmen.

Will anyone stand up for comics in Alberta this time around? I don’t know.

I do know it’s easy to score political points by attacking comics and graphic novels, since there are so few organizations set up to champion them, at least in Canada. We do not have an equivalent to the U.S. Comic Book Legal Defense Fund, which supports creators, retailers, and educators.

That said, I was encouraged to see that the Toronto Comics Art Festival spoke out against Smith’s lunacy.

“We cannot stand by while governments and school boards strip these stories from bookshelves,” the organization’s board said in a statement early this month. “This fight is about the freedom to read. It’s about whose stories we allow to be told, and whose stories we try to silence.”

I’m hoping others will follow TCAF’s example.

At a time when there is a global information source containing easy access to all kinds of actual hardcore pornography, it seems odd to single out graphic novels that young Albertans likely aren’t all that interested in reading in the first place. They’d rather be playing on their phones.

Dan Brown has covered pop culture for more than 33 years as a journalist and also moderates L.A. Mood’s monthly graphic-novel group.

Leave a comment